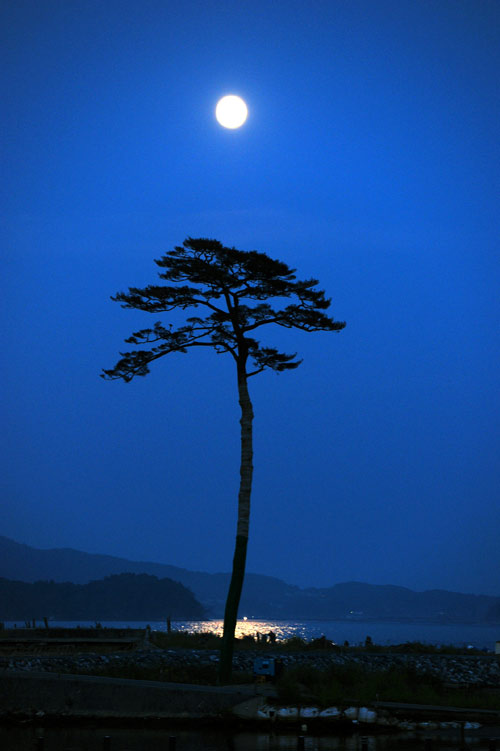

The Lone Pine by Nicolette Vajtay

THE LONE PINE is set in the true event of the 2011 tsunami in Japan, a commercial upmarket fiction at 93K words, a coming-of-age, multi-generational family saga that embodies the struggles of the human experience and the mystical muse of awakening.

At the heart of “The Lone Pine” stand three remarkable women of the Matsuoka family, each wrestling with their own burdens of loss and heartache, mirroring the intricate dance of the human experience.

Drawn from my personal encounters with upheaval and renewal, this narrative is a testament to our sometimes fallible but indomitable spirit, a spirit that empowers us to rise time and time again.

Michiko, an eleven-year-old biracial girl, is swept up in the chaos of the 2011 earthquake and subsequent tsunami while visiting her grandparents in Japan.

As the devastating wave reshapes their world, Michiko’s grandmother Azumi, and her mother Shizuko must not only face the destruction of their home but also confront the painful tensions within their family. Against the backdrop of a transforming landscape, they start a new life in America, navigating cultural differences, hidden family secrets, and the rigid patriarchal expectations of Michiko’s grandfather, Akio.

“The Lone Pine” will resonate with readers seeking stories that blend emotional depth with a rich tapestry of cultural and historical context. The Matsuoka women strive to forge a new sense of belonging amidst the ruins of their past. Michiko becomes the catalyst in breaking a multi-generational miasma of abuse and survival. In a single, transformative moment, driven by the unfathomable power of water as both creator and destroyer, the family is irrevocably reshaped, for better and for worse.

Currently seeking literary representation!

Read the first chapter below.

Email me

Chapter 1: ザ・余波

The Aftermath March 13, 2011

Michiko’s grandfather mumbled in his feverish sleep, weary with flu. Though wrapped in a heavy gray blanket, finding rest in the bow of the old red rowboat, she could see the pain of illness on his face. He does not look peaceful, Michiko thought. He wore the constant frown he wore when awake. In the long year she had lived with her grandparents in Japan, he had said so little, no more than a one-word scolding now and then. “Shinai (don’t),” he would say, or “Ie (no).” “Too curious,” he would announce into the room over her head directed at her grandmother. “That is a dangerous quality.”

Being estranged from their daughter for two decades, her grandparents didn’t even know they had a granddaughter until she arrived in Japan. And with a shock of blond hair and bright blue eyes, her grandfather doubted this little person belonged to his family at all. Aren’t grandfathers supposed to love their granddaughters by default, Michiko wondered. She couldn’t help that she looked like her father, no matter how much she wished she had her mother’s exotic almond-shaped eyes and jet-black hair. In comparison, Michiko felt ordinary.

Her grandfather may have been grouchy, but Michiko had liked him right away. She liked how he talked to the trees in the forest and how the pines rustled as if in response. He’d lay his hands on a tree with a firm touch, rub the needles between his fingers, or smell the air and the soil, every action filling his mind with volumes of information about the tree’s health or decline. She liked how he could tell the weather from looking at the stars. She even liked his frown. It made him appear distinguished, and it made her curious about his unhappiness. Deep creases underlined his dark, sad eyes, and dozens of gray hairs crossed the top of his head. Thin and limber, his body seemed strong and his will sturdy for his almost seventy years. One day, Michiko would grow beyond his five-foot-five-inches height. She would be tall like her father who surpassed six-two by three-quarters of an inch.

Her grandparents had lived on the northeast coast of Japan their entire lives. They raised a child, tended to the forest, and visited with family and friends. They never ventured further than the southern tip of the island, they didn’t have any money to travel. But they were content. Until two days ago, when a fifteen-meter wall of frigid black water, taller than the tallest building, wiped it all away. She was there. Michiko had seen it all with her own eyes, watched as the ocean dragged the entire village out into the raging sea. Some would say that Michiko had bad luck, immersed in such a tragedy when she should have been home in Hawaii.

That March morning her grandfather needed to see it, to see that all he knew and loved was gone. He tried to accept this as truth, but he could not, and he shrunk smaller and smaller with despair into the rowboat. While the thick blanket swallowed him whole, it did not keep out the flu’s chill, even with the profusion of heat that consumed them.

Hours passed as they swayed back and forth on the uneasy sea. While her grandfather slept like a wintering bear, Michiko sighed, queasy with seasickness. Even though a blazing ball of fire hung suspended in the sky above, Michiko’s teeth chattered as dread covered her body with chills. With no small bit of shade in any direction, Michiko turned her back to the sun. Sweat dripped down her neck and collected behind her knees. She was thirsty; so very thirsty. A million worries screamed in her head but just one question perched on her tongue. Why?

“Why?” had always been Michiko’s favorite question as a toddler, a question she asked a hundred times a day to anyone within a two-foot radius. Most often that person was her mother, from whom Michiko demanded answers with her hand planted on her right-cocked hip like a defiant teenager. Not any answers, but good ones, that made sense in her young mind. “Why do dogs eat grass? Why does it tickle under my arm? Why aren’t there any more dinosaurs? Why is that man sleeping on the sidewalk?”

Michiko could see everything from where she sat in the boat, the sea on her left, the village, where the village used to be, on her right. Higher on the mountain, she could see a definitive mark where the wave could no longer reach, a line that separated life from death. Above that line, trees with plump springtime buds turned toward the sun; the road wound its way around to the next village; glass windows in cozy homes sparked with morning light; the rugged schoolhouse and temple stood, untouched, both needing a new coat of paint.

Below that line, low in the valley, ravaged treasures lay half-submerged in a swamp of seawater. Twisted lengths of rebar protruded through shattered windshields of overturned cars. Chunks of wood and brick and drywall lay strewn over the landscape as if every house in the village had exploded. Splintered tables and broken chairs teetered atop cumbrous mounds of debris that blotted the once vibrant valley. She wanted to ask why but dared not wake her grandfather from his rest. She wanted to call her mother, tell her everything, but there wasn’t a single telephone line still strung from pole to pole. It was then, at the innocent age of ten, that Michiko realized that sometimes there is no answer to the question why.

She shielded her eyes with her hands and scanned the horizon for Kichiro, her only friend in the world. It had been two days since she’d seen him. She prayed for a glimpse of his bushy white tail wagging in the distance but saw nothing but mounds and mounds of rotting trash. Questions raced in her mind. Why didn’t he walk with me to school? Why wasn’t he in the garden when the sirens started screaming? Why did my grandparents leave the house without him? She hoped he had found some kind of safety, something solid to rest on. How long could a dog tread in freezing cold water? Not long, she imagined. Her nose stung as tears threatened to burst out of her eyes, but she shook her head, I will not cry, she promised herself and pushed those horrible thoughts out of her mind.

When her grandfather finally opened his tired eyes, he squinted up sideways at the throbbing summer sun in the cool spring sky. Then he looked at Michiko long and hard, so long, she thought he had fallen asleep again with his eyes open.

She couldn’t hold it in any longer. “Ojiisan, I want to help. What can I do? Would you teach me? Please?” she asked in perfect Japanese. He didn’t speak English, but Michiko had practiced his language since the age of three. Her mother taught her. And after living in Japan for a whole year, she had grown confident in her new vocabulary.

It took her grandfather many long minutes to untangle himself from the blanket and prop himself up into a sitting position. Michiko tried to hide her anticipation, which was quickly turning into impatience. When he finally settled, he nodded his head twice, once to acknowledge his inner consent, the other nod for Michiko. He would let her help.

She jumped up with a bit of glee, and landed on the seat closer to him, steadying herself before the rocking boat dumped her into the freezing waves. Once the boat settled, her grandfather began to impart a small bit from his canon of knowledge on how to build a kēson.

“What’s that?” she asked. She didn’t know that word.

His entire body shook as his lungs clenched and squeezed out spasms of raspy barks. When the coughing fit finally passed, he tried again to describe a kēson in his flu-soaked voice. Michiko had to lean in closer to hear him, and they both noticed that when she bent forward, he tilted further away. He wanted to pull her close and hold her in his arms, but his conditioned mind would not respond to his heart’s desire. He tried again to speak, but by then exhaustion had won and forced him back with a sigh that sounded like misery.

Michiko didn’t understand the big Japanese words he used – but giving up was not an option. If they were going to get anything done, she and her grandfather would have to communicate in a different way. But when she looked out toward the horizon, she questioned her own positivity. She sent a silent prayer to Kichiro, hoping he was somewhere safe, and followed a new idea out of the boat.

Resting her belly on the gunwale, she inched over the side of the boat and lowered herself into the salty surge. Goosebumps erupted up and down her submerged legs! Every nerve in her thighs and lower back sizzled as if on fire! With her arms held up by her shoulders, trying to keep some of her body dry, she sloshed through the sea toward dry land.

A white sock hung suspended under the surface. Michiko took a deep breath, as if breathing for that submerged sock. When she reached for it, to save it from its suffering, the tide pulled it under and out of sight. It’s a sock, she reminded herself and shook her head to clear her thoughts. A red envelope, a book, its pages long soaked and dissolved, a pair of jeans, and a child’s sippy cup, floated around her on the surface of the waves. A dead squirrel brushed her at her waist, forcing her to duck to her left into a cluster of tree branches that grabbed at her hair with anxious fingers. A few meters later she stepped onto dry land and shook off the wetness like she had seen Kichiro do a thousand times. She set out on her daunting task, her leather shoes squeaking with every step, salt and water oozing from her soaked knee socks.

When her grandfather woke again from his troubled sleep, he found Michiko settled in the boat, back on the seat closest to him as if she had never left. She held out a piece of drywall she had found in the debris, about the size of an encyclopedia, and stranger than strange, a number 2 yellow pencil.

“It won’t write,” she said. The tip had snapped off during its cruel journey in the harsh wave. “But I thought you could use it to scratch a drawing into the plaster.”

He shook his head from side to side, not in disagreement, but mystified by his granddaughter’s smart thinking. And at that moment, he made a quiet vow to himself, that he would know her in a way that he had never known his own daughter.

He shifted his tired body and propped himself into an upright position. The arduous effort rocked the boat again and Michiko’s stomach gurgled with nausea. Puddles on the bottom of the boat rippled from his movement, causing chipped flecks of red paint to swirl in the water and stick to her soaked school shoes. She stared down at her black penny loafers… and had a sudden realization they were her only pair of shoes. All the clothes she had left were on her body. The school uniform, with a blue-plaid skirt, a white blouse, and a dark blue sweater that she had tied around her waist. Every other thing from her small closet, her few toys, and several books, were all snatched by the greedy tsunami as it raced back into the sea. Along with her grandparent’s house, the shops, the cars, and the … and the people. What about all the people, she wondered and held her breath to hold back her tears.

Her grandfather adjusted the blanket over his shoulders, looked around then closed his eyes with a sigh as if he wished the misfortune away. Michiko fidgeted in her seat, growing anxious about his slow progress. Is he praying, she wondered. When he finally opened his eyes again, he trembled. Does he feel as scared as I? Then his head bobbed up and down in a nod as if he agreed to a conversation only in his mind.

His hand traveled to his belt and rested there on the old wood sheath that housed the knife on his hip. After another moment of contemplation, he pushed the weathered sheath down the length of his leather belt, tugged one final time, and it slid off into his hands. With delicate care, he pulled the weapon from its wooden home and the double-edged blade glinted with a spark of sunlight. A striking weapon called a Tantō, still as sharp that day as when the craftsman forged it for the Great Samurai Yuudai in the twelfth century.

Michiko had heard the mystical story about the Tantō, twice already. For almost a thousand years the Samurai’s family had passed the dagger from generation to generation to the first-born son. Each young boy received the knife when he turned ten years of age. Including her grandfather. It was no wonder he held the blade with such reverence, like a sacred family relic.

His ancestors, so her ancestors too, all believed the dagger possessed the powers of the spirit of the Samurai Yuudai. Her grandfather hadn’t subscribed to the supernatural, not till one day in his early thirties when he found himself in a deathly duel. He swore it was the Samurai who intervened and saved his life; he saw him with his own two eyes even if he didn’t believe in ghosts.

Another cough wracked her grandfather’s weak body, and the blade slipped from his hands, hitting the bottom of the boat, shattering the silence with a symphonic tone. The astonishing sound quieted Michiko’s heart with comfort. When she looked up, she saw that her grandfather had also paused, with true amazement in his eyes as he listened to the mystical music. With a contented sigh, he retrieved the dagger from the puddle and did something that took Michiko by complete surprise. He raised his arms and reached them out to her; the knife lay in his hands like an offering.

“Take it, Michiko, use it,” he said. “I pray the Great Samurai will help us today.”

Michiko didn’t understand. Her grandfather forbade her to even be near the dagger, let alone touch it. He had warned her over and over. “It is a powerful weapon, Michiko, and little girls must not touch! You must listen and obey.”

He sounded so much like her mother with her vigilance of caution droning in Michiko’s ears. She never understood how her mother could not understand that you needed a knife to carve boxes into forts, to cut water bugs in half, to dissect frogs.

Her grandfather moaned from the exertion it took to hold the blade, his arms weighted with the fatigue of flu.

“I don’t want it,” Michiko said and crawled over to the rear seat of the boat.

“I am too tired,” he said, “too weak to press the image upon the plaster. It will be easier to draw.” He held the dagger out to her with instructions to carve the pencil into a point.

She wouldn’t have trusted a ten-year-old like herself with such a weapon so why did he? Sure, she had whittled a stick in Girl Scouts, but her grandfather wouldn’t have known that. The master had crafted the Tantō to kill, not to sharpen a pencil.

Her grandfather used all his remaining energy, leaned toward her, and pushed the shaft of the Tantō into her small hand. She wanted to give it back, but his face flared red as his lungs coughed up a spasm of searing need. Michiko reached out to him, but he shook her off and leaned back again, wrapped the blanket tighter around his shoulders, and directed her attention to the blade. She looked straight into his dark eyes for confirmation, and while clouded with fever, they were clear with intention.

“Leave me be. Get on with your task,” he said, then closed his eyes in search of some relief.

Sitting there on the rear seat of the boat, Michiko passed the weapon back and forth between her two hands, taking a moment to consider its immense danger. And its beauty. The weapon felt much heavier than she expected, but it also felt natural in her hands, as if she had held it a million times before. Without ever having seen such a weapon, she somehow knew how to hold it, which both surprised her and not. From the very first time she saw the dagger, she felt a connection to it, like in some strange way it had always belonged to her.

When she touched the blade to the edge of the broken pencil, the knife began to vibrate, and a gentle tingling tickled her fingers. Magic and joy and suspicion and awe and doubt and surprise all coursed through her mind at once. She thought she should have been afraid, but she was too excited. The teeth on the knife’s edge carved the lead with ease as if it sliced through a sweet summer peach. Razor-thin shavings of wood floated down into the boat like a cloud of butterflies. Michiko smiled, it must be the magic of the Samurai, she thought. At that moment, she accepted her grandfather’s story as truth, that the Great Yuudai had infused his Spirit into the dagger. It was he who carved the pencil, not her.

From the corner of her eye, she saw her grandfather watching as she carved the pencil. His wrinkled features softened, and a noticeable turn lifted his constant frown. He hadn’t expressed any emotion toward her before; the surprise of it made her feel self-conscious. When he nodded with approval, she fumbled, and the knife lurched in her hand. With a gentle touch, he placed two fingers on that soft spot below her thumb with a suggestion that she slow down.

Michiko’s concentration slipped away from the knife to the mound on her hand, where rough calluses scratched at that soft place under her thumb. It made her wonder about the harsh labor his hands performed. When he caught her looking at him, he glanced away, uncomfortable in such an unguarded moment, and rested back again into the bow of the boat. On that day, after living in his home for over a year, her grandfather had touched her hand for the first time.

After a few more passes over the lead, Michiko presented the pencil to her grandfather with a point so finely carved, it could write a novel.